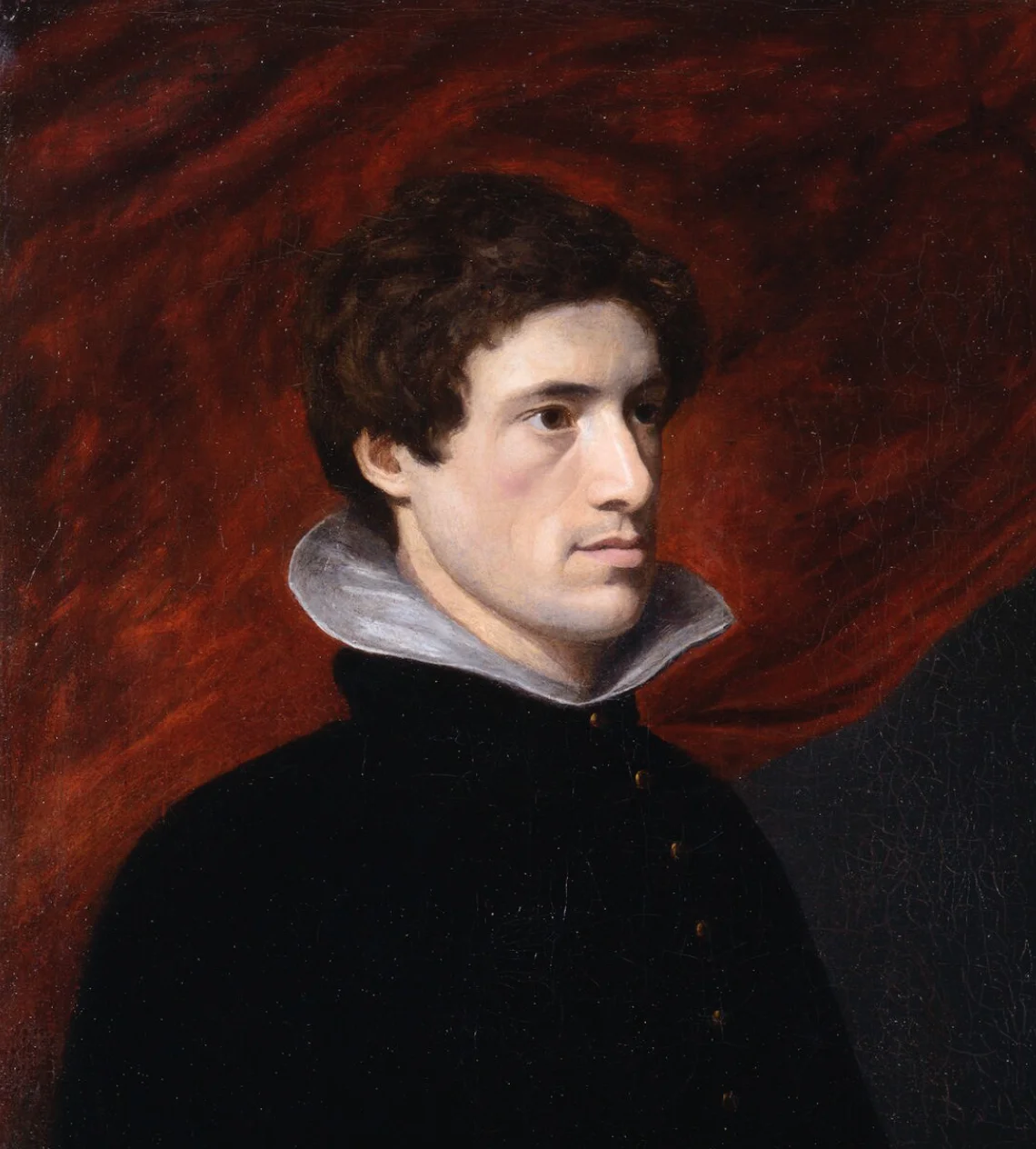

LAMB, CHARLES (1775-1834)

LAMB, CHARLES (1775-1834), English essayist and critic, was born in Crown Office Row, Inner Temple, London, on the 10th of February 1775. His father, John Lamb, a Lincolnshire man, who filled the situation of clerk and servant-companion to Samuel Salt, a member of parliament and one of the benchers of the Inner Temple, was successful in obtaining for Charles, the youngest of three surviving children, a presentation to Christ’s Hospital, where the boy remained from his eighth to his fifteenth year (1782-1789). Here he had for a schoolfellow Samuel Taylor Coleridge, his senior by rather more than two years, and a close and tender friendship began which lasted for the rest of the lives of both. When the time came for leaving school, where he had learned some Greek and acquired considerable facility in Latin composition, Lamb, after a brief stay at home (probably spent, as his school holidays had often been, over old English authors in Salt’s library) was condemned to the labours of the desk—an inconquerable impediment

in his speech disqualifying him for the clerical profession, which, as the school exhibitions were usually only given to those preparing for the church, thus deprived him of the only means by which he could have obtained a university education. For a short time he was in the office of Joseph Paice, a London merchant, and then for twenty-three weeks, until the 8th of February 1792, he held a small post in the Examiner’s Office of the South Sea House, where his brother John was established, a period which, although his age was but sixteen, was to provide him nearly thirty years later with materials for the first of the Essays of Elia. On the 5th of April 1792, he entered the Accountant’s Office in the East India House, where during the next three and thirty years the hundred official folios of what he used to call his true works

were produced.

Of the years 1792-1795 we know little. At the end of 1794 he saw much of Coleridge and joined him in writing sonnets in the Morning Post, addressed to eminent persons: early in 1795 he met Southey and was much in the company of James White, whom he probably helped in the composition of the Original Letters of Sir John Falstaff; and at the end of the year for a short time he became so unhinged mentally as to necessitate confinement in an asylum. The cause, it is probable, was an unsuccessful love affair with Ann Simmons, the Hertfordshire maiden to whom his first sonnets are addressed, whom he would have seen when on his visits as a youth to Blakesware House, near Widford, the country home of the Plumer family, of which Lamb’s grandmother, Mary Field, was for many years, until her death in 1792, sole custodian.

It was in the late summer of 1796 that a dreadful calamity came upon the Lambs, which seemed to blight all Lamb’s prospects in the very morning of life. On the 22nd of September his sister Mary, worn down to a state of extreme nervous misery by attention to needlework by day and to her mother at night,

was suddenly seized with acute mania, in which she stabbed her mother to the heart. The calm self-mastery and loving self-renunciation which Charles Lamb, by constitution excitable, nervous and self-mistrustful, displayed at this crisis in his own history and in that of those nearest him, will ever give him an imperishable claim to the reverence and affection of all who are capable of appreciating the heroisms of common life. With the help of friends he succeeded in obtaining his sister’s release from the lifelong restraint to which she would otherwise have been doomed, on the express condition that he himself should undertake the responsibility for her safe keeping. It proved no light charge: for though no one was capable of affording a more intelligent or affectionate companionship than Mary Lamb during her periods of health, there was ever present the apprehension of the recurrence of her malady; and when from time to time the premonitory symptoms had become unmistakable, there was no alternative but her removal, which took place in quietness and tears. How deeply the whole course of Lamb’s domestic life must have been affected by his singular loyalty as a brother needs not to be pointed out.

Lamb’s first appearance as an author was made in the year of the great tragedy of his life (1796), when there were published in the volume of Poems on Various Subjects by Coleridge four sonnets by Mr Charles Lamb of the India House.

In the following year he contributed, with Charles Lloyd, a pupil of Coleridge, some pieces in blank verse to the second edition of Coleridge’s Poems. In 1797 his short summer holiday was spent with Coleridge at Nether Stowey, where he met the Wordsworths, William and Dorothy, and established a friendship with both which only his own death terminated. In 1798, under the influence of Henry Mackenzie’s novel Julie de Roubigné, he published a short and pathetic prose tale entitled Rosamund Gray, in which it is possible to trace beneath disguised conditions references to the misfortunes of the author’s own family, and many personal touches; and in the same year he joined Lloyd in a volume of Blank Verse, to which Lamb contributed poems occasioned by the death of his mother and his aunt Sarah Lamb, among them being his best-known lyric, The Old Familiar Faces. In this year, 1798, he achieved the unexpected publicity of an attack by the Anti-Jacobin upon him as an associate of Coleridge and Southey (to whose Annual Anthology he had contributed) in their Jacobin machinations. In 1799, on the death of her father, Mary Lamb came to live again with her brother, their home then being in Pentonville; but it was not until 1800 that they really settled together, their first independent joint home being at Mitre Court Buildings in the Temple, where they lived until 1809. At the end of 1801, or beginning of 1802, appeared Lamb’s first play John Woodvil, on which he set great store, a slight dramatic piece written in the style of the earlier Elizabethan period and containing some genuine poetry and happy delineation of the gentler emotions, but as a whole deficient in plot, vigour and character; it was held up to ridicule by the Edinburgh Review as a specimen of the rudest condition of the drama, a work by a man of the age of Thespis.

The dramatic spirit, however, was not thus easily quenched in Lamb, and his next effort was a farce, Mr H——, the point of which lay in the hero’s anxiety to conceal his name Hogsflesh

; but it did not survive the first night of its appearance at Drury Lane, in December 1806. Its author bore the failure with rare equanimity and good humour—even to joining in the hissing—and soon struck into new and more successful fields of literary exertion. Before, however, passing to these it should be mentioned that he made various efforts to earn money by journalism, partly by humorous articles, partly as dramatic critic, but chiefly as a contributor of sarcastic or funny paragraphs, sparing neither man nor woman,

in the Morning Post, principally in 1803.

In 1807 appeared Tales founded on the Plays of Shakespeare, written by Charles and Mary Lamb, in which Charles was responsible for the tragedies and Mary for the comedies; and in 1808, Specimens of English Dramatic Poets who lived about the time of Shakespeare, with short but felicitous critical notes. It was this work which laid the foundation of Lamb’s reputation as a critic, for it was filled with imaginative understanding of the old playwrights, and a warm, discerning and novel appreciation of their great merits. In the same year, 1808, Mary Lamb, assisted by her brother, published Poetry for Children, and a collection of short school-girl tales under the title Mrs Leicester’s School; and to the same date belongs The Adventures of Ulysses, designed by Lamb as a companion to The Adventures of Telemachus. In 1810 began to appear Leigh Hunt’s quarterly periodical, The Reflector, in which Lamb published much (including the fine essays on the tragedies of Shakespeare and on Hogarth) that subsequently appeared in the first collective edition of his Works, which he put forth in 1818.

Between 1811, when The Reflector ceased, and 1820, he wrote almost nothing. In these years we may imagine him at his most social period, playing much whist and entertaining his friends on Wednesday or Thursday nights; meanwhile gathering 105 that reputation as a conversationalist or inspirer of conversation in others, which Hazlitt, who was at one time one of Lamb’s closest friends, has done so much to celebrate. When in 1818 appeared the Works in two volumes, it may be that Lamb considered his literary career over. Before coming to 1820, and an event which was in reality to be the beginning of that career as it is generally known—the establishment of the London Magazine—it should be recorded that in the summer of 1819 Lamb, with his sister’s full consent, proposed marriage to Fanny Kelly, the actress, who was then in her thirtieth year. Miss Kelly could not accept, giving as one reason her devotion to her mother. Lamb bore the rebuff with characteristic humour and fortitude.

The establishment of the London Magazine in 1820 stimulated Lamb to the production of a series of new essays (the Essays of Elia) which may be said to form the chief corner-stone in the small but classic temple of his fame. The first of these, as it fell out, was a description of the old South Sea House, with which Lamb happened to have associated the name of a gay light-hearted foreigner

called Elia, who was a clerk in the days of his service there. The pseudonym adopted on this occasion was retained for the subsequent contributions, which appeared collectively in a volume of essays called Elia, in 1823. After a career of five years the London Magazine came to an end; and about the same period Lamb’s long connexion with the India House terminated, a pension of £450 (£441 net) having been assigned to him. The increased leisure, however, for which he had long sighed, did not prove favourable to literary production, which henceforth was limited to a few trifling contributions to the New Monthly and other serials, and the excavation of gems from the mass of dramatic literature bequeathed to the British Museum by David Garrick, which Lamb laboriously read through in 1827, an occupation which supplied him for a time with the regular hours of work he missed so much. The malady of his sister, which continued to increase with ever shortening intervals of relief, broke in painfully on his lettered ease and comfort; and it is unfortunately impossible to ignore the deteriorating effects of an over-free indulgence in the use of alcohol, and, in early life, tobacco, on a temperament such as his. His removal on account of his sister to the quiet of the country at Enfield, by tending to withdraw him from the stimulating society of the large circle of literary friends who had helped to make his weekly or monthly at homes

so remarkable, doubtless also tended to intensify his listlessness and helplessness. One of the brightest elements in the closing years of his life was the friendship and companionship of Emma Isola, whom he and his sister had adopted, and whose marriage in 1833 to Edward Moxon, the publisher, though a source of unselfish joy to Lamb, left him more than ever alone. While living at Edmonton, whither he had moved in 1833 so that his sister might have the continual care of Mr and Mrs Walden, who were accustomed to patients of weak intellect, Lamb was overtaken by an attack of erysipelas brought on by an accidental fall as he was walking on the London road. After a few days’ illness he died on the 27th of December, 1834. The sudden death of one so widely known, admired and beloved, fell on the public as well as on his own attached circle with all the poignancy of a personal calamity and a private grief. His memory wanted no tribute that affection could bestow, and Wordsworth commemorated in simple and solemn verse the genius, virtues and fraternal devotion of his early friend.

Charles Lamb is entitled to a place as an essayist beside Montaigne, Sir Thomas Browne, Steele and Addison. He unites many of the characteristics of each of these writers—refined and exquisite humour, a genuine and cordial vein of pleasantry and heart-touching pathos. His fancy is distinguished by great delicacy and tenderness; and even his conceits are imbued with human feeling and passion. He had an extreme and almost exclusive partiality for earlier prose writers, particularly for Fuller, Browne and Burton, as well as for the dramatists of Shakespeare’s time; and the care with which he studied them is apparent in all he ever wrote. It shines out conspicuously in his style, which has an antique air and is redolent of the peculiarities of the 17th century. Its quaintness has subjected the author to the charge of affectation, but there is nothing really affected in his writings. His style is not so much an imitation as a reflexion of the older writers; for in spirit he made himself their contemporary. A confirmed habit of studying them in preference to modern literature had made something of their style natural to him; and long experience had rendered it not only easy and familiar but habitual. It was not a masquerade dress he wore, but the costume which showed the man to most advantage. With thought and meaning often profound, though clothed in simple language, every sentence of his essays is pregnant.

He played a considerable part in reviving the dramatic writers of the Shakesperian age; for he preceded Gifford and others in wiping the dust of ages from their works. In his brief comments on each specimen he displays exquisite powers of discrimination: his discernment of the true meaning of his author is almost infallible. His work was a departure in criticism. Former editors had supplied textual criticism and alternative readings: Lamb’s object was to show how our ancestors felt when they placed themselves by the power of imagination in trying situations, in the conflicts of duty or passion or the strife of contending duties; what sorts of loves and enmities theirs were.

As a poet Lamb is not entitled to so high a place as that which can be claimed for him as essayist and critic. His dependence on Elizabethan models is here also manifest, but in such a way as to bring into all the greater prominence his native deficiency in the accomplishment of verse.

Yet it is impossible, once having read, ever to forget the tenderness and grace of such poems as Hester, The Old Familiar Faces, and the lines On an infant dying as soon as born or the quaint humour of A Farewell to Tobacco. As a letter writer Lamb ranks very high, and when in a nonsensical mood there is none to touch him.

Editions and memoirs of Lamb are numerous. The Letters, with a sketch of his life by Sir Thomas Noon Talfourd, appeared in 1837; the Final Memorials of Charles Lamb by the same hand, after Mary Lamb’s death, in 1848; Barry Cornwall’s Charles Lamb: A Memoir, in 1866. Mr P. Fitzgerald’s Charles Lamb: his Friends, his Haunts and his Books (1866); W. Carew Hazlitt’s Mary and Charles Lamb (1874). Mr Fitzgerald and Mr Hazlitt have also both edited the Letters, and Mr Fitzgerald brought Talfourd to date with an edition of Lamb’s works in 1870-1876. Later and fuller editions are those of Canon Ainger in 12 volumes, Mr Macdonald in 12 volumes and Mr E. V. Lucas in 7 volumes, to which in 1905 was added The Life of Charles Lamb, in 2 volumes.

(E. V. L.) [Edward Verrall Lucas]